Key Takeaways:

- More and more the current environment looks like the Tech Bubble of the late 1990s.

- Oracle has announced a huge deal for cloud computing infrastructure with OpenAI to the tune of $300 billion, but neither Oracle nor OpenAI appear capable of financing the deal.

- The prospective economics of the deal and assumptions that form the basis for the massive spending appear more and more aggressive, akin to the Fiber buildout which occurred in the late 90s.

Oracle Ups the Ante in the AI Arms Race

If the Tech Bubble of the late-90s had Beanie Babies, the AI bubble of the 2020s now has Labubus[1]. The ugly-cute monster dolls have captured the attention of the TikTok generation and become this era’s collectible. The parallels between the two time periods seem to be becoming more and more unmistakable.

While it is too early to know which companies or investment deals will be the “butt of the joke” in this cycle – akin to the dubious AOL/Time Warner merger or Level 3 Communications which spent billions to build the backbone for the internet on Fiber that wouldn’t be needed for many years – we are continuing to see evidence of the same growth-hungry capital spending boom.

The latest business to make a splash in the AI arms race was Oracle. On September 9th they reported their quarterly earnings and, while the results were relatively uninspiring and would have otherwise been a non-market event, they disclosed a staggering and unexpected $455 billion in remaining performance obligations (RPO)[2], an accounting term for contracted future revenue. This sent their stock up nearly 40%, or about $300 billion, one of the largest one-day gains in history[3]. The RPO was an increase of $317 billion from the prior quarter, almost entirely due to a $300 billion deal to build datacenters for OpenAI. In Oracle’s updated financial projections, they estimated their Cloud Infrastructure revenue could increase almost tenfold in the next five years, which is likely the term of the contract with OpenAI.

It is no surprise that investors were giddy over these results, as it’s a clear and unexpected step change in growth, putting Oracle’s future revenue in the ballpark of the current cloud computing titans Microsoft and AWS. While this certainly supports the idea that the firms who are at the leading edge of AI have not reached the limit of their voracious appetite for computing power, it also raises a lot of questions. Particularly, how such a large sum will be financed by a money-losing start-up (Open AI) or even how Oracle, albeit a very large and profitable business, would fund the necessary capacity to serve the contract. While there are no public details on the actual economics of the deal, presumably Oracle had to bid aggressively to win such a large contract. While this is being viewed bullishly by the market, we expect this deal could end up looking like the overbuilding of Fiber which occurred during the telecom bubble in the late 1990s.

Oracle Over the Years: From Capital Light to Capital Intensive

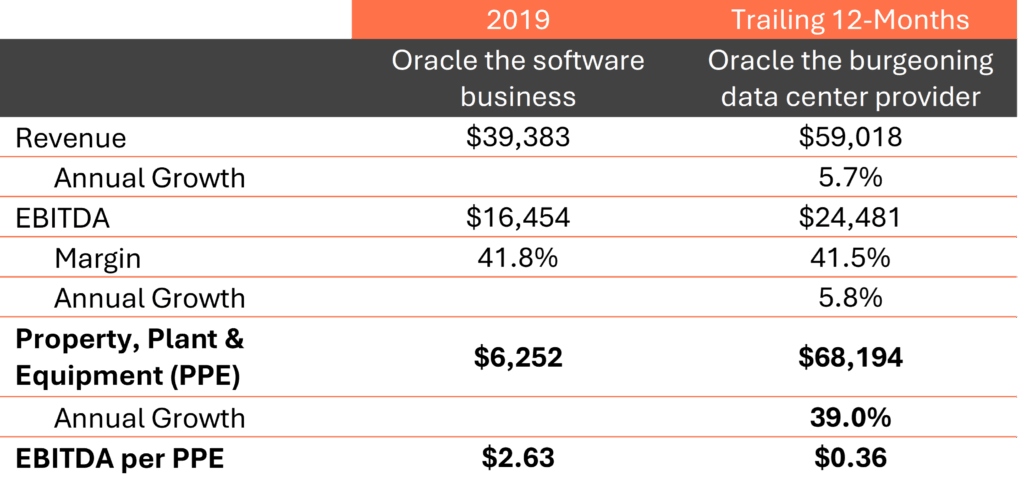

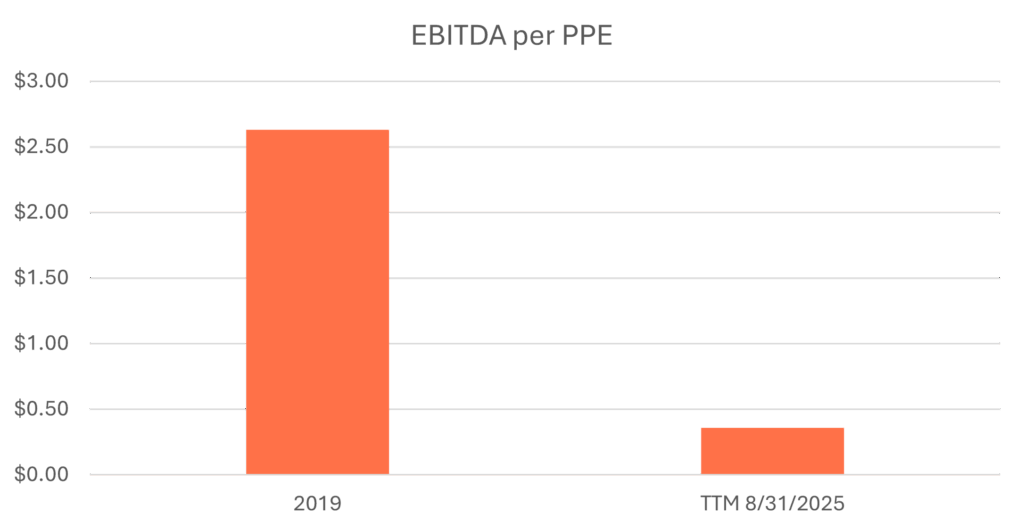

Historically, Oracle had the envious economics of a software company – high margins and very little capital required to run its business. Over the years, as Oracle has attempted to compete more aggressively in the Cloud infrastructure business, it has become materially more capital intensive. In the past, every $1 invested in property, plant and equipment yielded over $2.6 in Profit (EBITDA or (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) – an astounding result in line with the enviable economics of a software business. Over the past six years, as profits have grown moderately, the capital required to run the business has grown 10x to the point that the same dollar of equipment yields just $0.36 of profit.[4]

Source: Bloomberg, Oracle public filings: 2019 10k, the last three 10Qs, and the 2025 10k.

Source: Bloomberg, Oracle public filings: 2019 10k, the last three 10Qs, and the 2025 10k.

Is the OpenAI Contract Good Business?

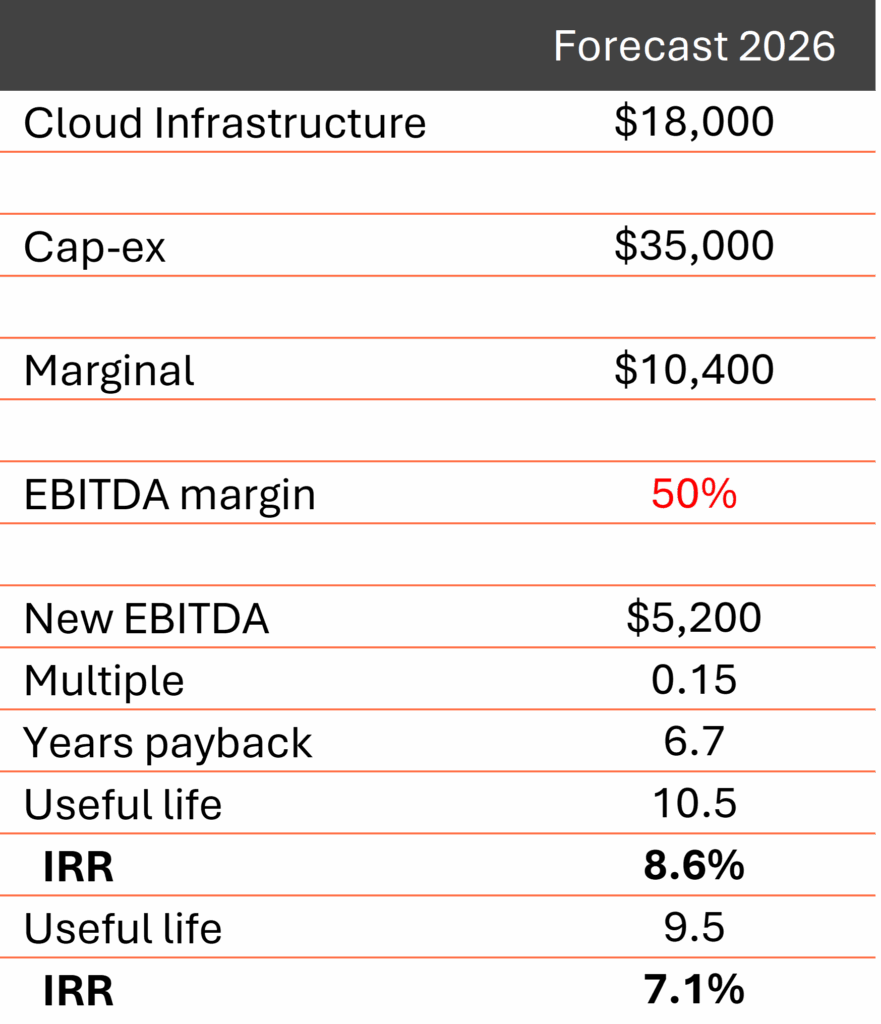

Without knowing the terms of the agreement we can only speculate on the economics, but presumably such a large contract was very competitive. Oracle has offered hints based on its forecasts. In the current year they now expect $18 billion in revenue in their cloud infrastructure business (an increase of $10.4 billion in the year) and expect $35 billion in capital expenditures (Cap-Ex). If we assume all of this Cap-Ex is for Cloud infrastructure and they make a relatively generous 50% profit margin, they might be generating $0.15 in profit for every dollar they have to spend. These are much lower returns than their historic business but still potentially acceptable assuming the spend doesn’t need to be replaced too quickly.[5]

Source: Personal assumptions and Oracles Fiscal Q1 2026 press release.

Source: Personal assumptions and Oracles Fiscal Q1 2026 press release.But that may be a faulty assumption given just how quickly Nvidia is trying to improve its cutting-edge chips with a new chipset released roughly every two years. Based on Oracle’s own estimates, their equipment should last over 10 years (the chips six years and the rest about 15 years) which would yield a relatively uninspiring 8.6% return on capital. If we assume the chips don’t last a full six years and reduce that to four years, to account for how quickly Nvidia is trying to obsolete its own older chips, then that return gets quite poor at 7.1%[6].

How Much Will it Cost?

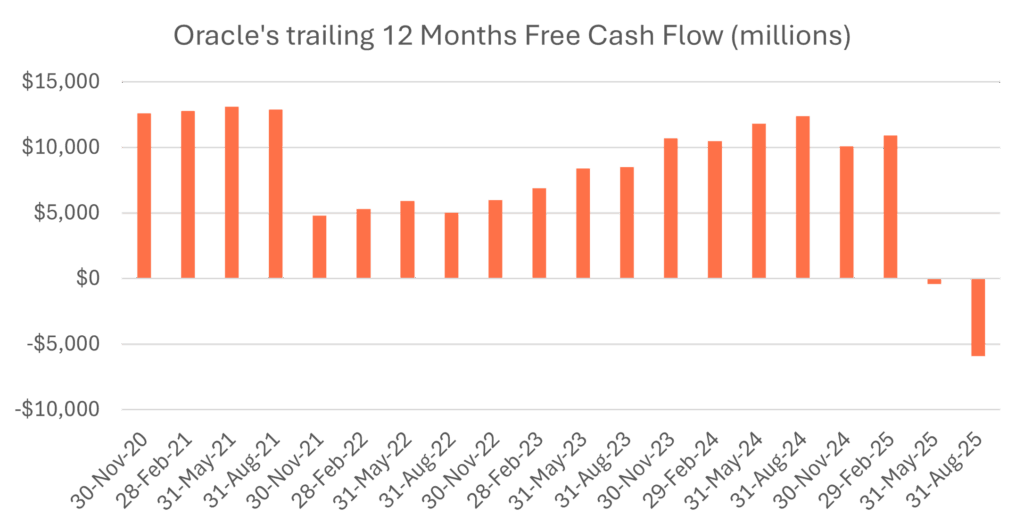

By my estimate, Oracle may need to spend at least $185 billion to fulfill their astounding 2030 revenue target of $144 billion within their cloud infrastructure business. Oracle has a nicely profitable existing business to help fund this, but their cash flow has already gone negative as they begin this massive investment cycle.

Source: Bloomberg, Oracle regulatory filings 10qs and 10ks. 11/30/2020 – 8/31/2025

Source: Bloomberg, Oracle regulatory filings 10qs and 10ks. 11/30/2020 – 8/31/2025

That $185 billion is 7.5x their trailing 12 months EBITDA (a useful ratio for ability to spend/pay down debt) and they have already raised roughly $100 billion in debt – 4x their EBITDA, a relatively high amount of leverage for any business and almost unheard of for a software business. It won’t be easy to raise the capital needed, although their new market cap should help! It’s likely there will be some interesting and creative solution to help fund this, such as the recent deal between Nvidia and Coreweave in which Nvidia has essentially backstopped Coreweave’s purchase of Nvidia’s chips. Coreweave has also managed to secure loans collateralized by Nvidia chips[7].

As long as the appetite for AI investment remains hot there will likely be creative (and very risky options) for financing this growth.

How Does This Compare to the Incumbent Cloud Leaders?

None of this is to pick on Oracle either, the business of building data centers for the AI boom is a big growing industry, and other competitors appear to be chasing similar economics. In many cases, the customers of new data center businesses have their own data center businesses, and they are seemingly happy to outsource some of this investment anyway, implying they aren’t optimistic about the returns compared to the rest of their businesses. The aforementioned Coreweave, a pure play AI data center company, reported an increase of $5.5 billion in Property, Plant and Equipment (PP&E) in the last six months while its annualized Revenue increased $1.8 billion and EBITDA $838 million for a return of $0.15 for each dollar of PP&E invested – almost exactly what we worked out from Oracle’s estimates. Amazon’s AWS business, which is broken out explicitly in regulatory filings, earned $0.46 for every $1 of PP&E in its business – a number that has been quite higher in the past.[8]

Based on these numbers, it is clear the reality of the AI data center business is that it is a much lower return business than the established Cloud computing businesses. This could be a result of the nature of the business or simply because so much capital is chasing what has been deemed such a large growth industry.

Echos of the Dot-com Era

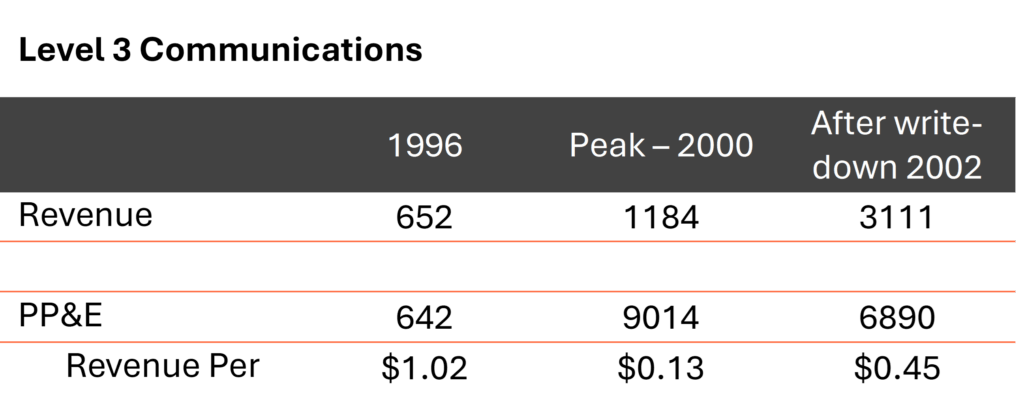

Chasing relatively low returning businesses in a market that is rewarding growth above all else is often great for stocks. In the end, however, the economics will dictate the future profits of a business, something investors will have to reconcile in time. Investing large amounts of capital at relatively low prospective returns leaves very little margin for error. If Open AI has trouble financing this deal and Oracle finds itself with too much capacity, they could easily end up having negative returns on their investment. In many ways, this epitomizes the Dotcom Bubble when Fiber companies rushed to spend on infrastructure to power the internet. Level 3 Communications was a posterchild of this and here is a snapshot of how their business developed over the period:

Source: Bloomberg, Level 3 public filings 10ks for 1996, 2000 and 2002.

Source: Bloomberg, Level 3 public filings 10ks for 1996, 2000 and 2002.

At the peak, with an assumed EBITDA margin of 50%, they were looking at 30 years to re-coup their investment. As the bubble unwound, they wrote down over $3 billion of their investments, mostly on undersea cables, and the economics became a bit more tenable. During this time Level 3 raised over $7 billion in debt to fund this build-out and the stock rose 11-fold before falling 95% (1/20th). I doubt Oracle will suffer such a fate, but it is rare that aggressive capital investment ends in aggressive returns on capital and at minimum, substantially increases the risks (and the growth too!) of all the participants.

Disclosures:

Copyright © 2025 Algorithmic Investment Models LLC. All rights reserved. All materials appearing in this commentary are protected by copyright as a collective work or compilation under U.S. copyright laws and are the property of Algorithmic Investment Models. You may not copy, reproduce, publish, use, create derivative works, transmit, sell or in any way exploit any content, in whole or in part, in this commentary without express permission from Algorithmic Investment Models.

Certain information contained herein constitutes “forward-looking statements,” which can be identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “intend,” “continue,” or “believe,” or the negatives thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events, results or actual performance may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Nothing contained herein may be relied upon as a guarantee, promise, assurance or a representation as to the future.

This material is provided for informational purposes only and does not in any sense constitute a solicitation or offer for the purchase or sale of a specific security or other investment options, nor does it constitute investment advice for any person. The material may contain forward or backward-looking statements regarding intent, beliefs regarding current or past expectations. The views expressed are also subject to change based on market and other conditions. The information presented in this report is based on data obtained from third party sources. Although it is believed to be accurate, no representation or warranty is made as to its accuracy or completeness.

The charts and infographics contained in this blog are typically based on data obtained from third parties and are believed to be accurate. The commentary included is the opinion of the author and subject to change at any time. Any reference to specific securities or investments are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended as investment advice nor are they a recommendation to take any action. Individual securities mentioned may be held in client accounts. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

As with all investments, there are associated inherent risks including loss of principal. Stock markets, especially foreign markets, are volatile and can decline significantly in response to adverse issuer, political, regulatory, market, or economic developments. Sector and factor investments concentrate in a particular industry or investment attribute, and the investments’ performance could depend heavily on the performance of that industry or attribute and be more volatile than the performance of less concentrated investment options and the market as a whole. Securities of companies with smaller market capitalizations tend to be more volatile and less liquid than larger company stocks. Foreign markets, particularly emerging markets, can be more volatile than U.S. markets due to increased political, regulatory, social or economic uncertainties. Fixed Income investments have exposure to credit, interest rate, market, and inflation risk. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against a loss.

Algorithmic Investment Models LLC (AIM)

125 Newbury St., 4th Floor, Boston, MA 02116 (844-401-7699)

[2] Oracle investor relations Q4 earnings press release. They estimated $18B in cloud infrastructure revenue for Fiscal 2026 and $144 billion for 2030.

[3] These are hand-wavy but accurate estimates can just cite Bloomberg

[4] Bloomberg, Oracle public filings: 2019 10k, the last three 10Qs, and the 2025 10k.

[5] Personal assumptions and Oracles Fiscal Q1 2026 press release.

[6] Within the crypto mining industry, chips are typically depreciated on a 2- or 3-year basis as returns completely drop off with older equipment.

[7] https://www.reuters.com/business/coreweave-nvidia-sign-63-billion-cloud-computing-capacity-order-2025-09-15/

[8] Bloomberg, Coreweave regulatory filings – S1 and Q125 10q.